“Open review and open peer review are new terms for evolving phenomena. They don’t have precise or technical definitions. No matter how they’re defined, there’s a large area of overlap between them. If there’s ever a difference, some kinds of open review accept evaluative comments from any readers, even anonymous readers, while other kinds try to limit evaluative comments to those from ”peers“ with expertise or credentials in the relevant field. But neither kind of review has a special name, and I think each could fairly be called “open review” or “open peer review”.” – Peter Suber, email correspondence, 20071.

As the realm of “open science” expands (Pontika et al., 2015), “open peer review” (OPR) emerges as a critical and actively discussed topic. Scholarly literature on defining open peer review is rapidly growing, yet, as numerous experts have pointed out (Ford, 2013; Hames, 2014; Ware, 2011), a universally accepted definition or a standardized framework of features for OPR remains absent. This lack of clarity is mirrored in the existing literature, which presents a diverse and sometimes conflicting array of definitions.

For some, open peer review refers to systems where both author and reviewer identities are known to each other. For others, it denotes systems where reviewer reports are published alongside the articles. Still others define open peer review as encompassing both identity disclosure and report publication, or even extending to systems that allow comments from a broader audience beyond invited experts. The term is also used to describe various combinations of these and other innovative approaches to peer review. A previous significant attempt to systematically unify these elements into a cohesive definition (Ford, 2013), which we will discuss later, unfortunately complicates rather than clarifies the issue.

In essence, the situation regarding the definition of open peer review hasn’t significantly improved since Suber’s insightful observation. This ongoing ambiguity becomes increasingly problematic as time progresses. Mark Ware aptly notes that “it is not always clear in debates over the merits of OPR exactly what is being referred to” (Ware, 2011). The varied forms of OPR incorporate independent elements such as open identities, open reports, and open participation, which are not inherently linked and possess distinct advantages and disadvantages. Consequently, evaluating the effectiveness of these different variables and comparing diverse systems becomes challenging. Discussions can easily be derailed when broad claims are made about the efficacy of “OPR” in general, while critiques often target a specific aspect or configuration of open peer review. It’s even plausible to argue that this definitional ambiguity hinders the development of a unified vision for “open evaluation” (OE) and an OE movement comparable to the open access (OA) movement, as Nicholas Kriegskorte has suggested (Kriegeskorte, 2012).

To address this definitional challenge, this article undertakes a systematic review of existing definitions of “open peer review” or “open review,” creating a corpus of over 120 definitions. These definitions are rigorously analyzed to construct a coherent typology of the various peer review innovations signified by the term. The aim is to provide the precise, technical definition that is currently lacking. This data-driven analysis reveals valuable insights into the range and evolution of different definitions across time and subject areas. Based on this comprehensive analysis, we propose a pragmatic definition of OPR as an overarching term encompassing various overlapping approaches to adapt peer review in alignment with Open Science objectives. These adaptations include making reviewer and author identities transparent, publishing review reports, and broadening participation in the peer review process.

Background

1. Problems with Peer Review

Peer review serves as the formal quality control mechanism in academia. Scholarly works, including journal articles, books, grant proposals, and conference papers, are subjected to scrutiny by experts. Their feedback and judgments are crucial for improving these works and making informed decisions about selection for publication, grant allocation, or presentation opportunities. Peer review traditionally fulfills two main roles: (1) technical evaluation of a work’s validity and soundness, focusing on methodology, analysis, and argumentation (“is it good scholarship?”), and (2) assisting editorial selection by assessing novelty and potential impact (“is it exciting, innovative, or important scholarship?”, “is it suitable for this journal, conference, or funding call?”). It is important to note that these two functions can be separated. Journals like PLOS ONE and PeerJ, for instance, have adopted models where reviewers primarily focus on technical soundness.

This widespread system is surprisingly recent, with its formal elements largely implemented in scientific publishing from the mid-20th century (Spier, 2002). While researchers generally agree on the necessity of peer review per se, dissatisfaction with the current model is prevalent. Ware’s 2008 survey, for example, indicated that a vast majority (85%) believe “peer review greatly helps scientific communication” and even more (around 90%) felt their own published work had been improved by peer review. However, nearly two-thirds (64%) expressed dissatisfaction with the current peer review system, and less than a third (32%) considered it the optimal system (Ware, 2008). A subsequent study by the same author indicated a slight increase in the desire for peer review improvements (Ware, 2016).

The widespread perception of the current model being suboptimal stems from various criticisms leveled against traditional peer review. These critiques operate at different levels, concerning both the performance of peer reviewers and editorial decisions influenced by or based on peer review. Below is a brief overview of these common criticisms of traditional peer review:

- Unreliability and inconsistency: Studies suggest significant inconsistencies in peer review judgments. Different reviewers evaluating the same manuscript often reach different conclusions and recommendations (Cicchetti, 1991; Rothwell & Martyn, 2000).

- Delay and expense: The peer review process can be lengthy and costly. It introduces significant delays in the dissemination of research findings and incurs substantial costs for the academic publishing system (Armstrong, 1982).

- Lack of accountability and risks of subversion: Traditional peer review, especially in single-blind and double-blind models, can lack transparency and accountability. Reviewers may not always be held responsible for biased or unsubstantiated critiques. Furthermore, the system is susceptible to various forms of subversion, including bias, conflicts of interest, and unethical practices (Rennie, 1998).

- Social and publication biases: Evidence suggests that peer review can be biased against certain authors based on factors like gender, institutional affiliation, geographical location, or novelty of the research (Horrobin, 1990; Lee et al., 2013).

- Lack of incentives for reviewers: Reviewing is often an unrewarded and undervalued activity within academia. Reviewers receive limited formal recognition for their time and effort, despite its crucial role in maintaining scholarly quality (Warne, 2016).

- Wastefulness: The reports generated during peer review, which often contain valuable insights and constructive feedback, are typically discarded after the publication decision. This represents a wasted opportunity to leverage potentially useful scholarly information (Armstrong, 1982).

In response to these criticisms, numerous modifications to peer review have been proposed (see comprehensive overviews in Tennant et al., 2017; Walker & Rocha da Silva, 2015). Many of these innovations have, at various times, been labeled as “open peer review.” As we will explore, the innovations termed OPR actually encompass a wide range of distinct approaches to “opening up” peer review. Each of these distinct features is theoretically intended to address one or more of the shortcomings listed above. However, no single feature claims to resolve all issues, and their aims may sometimes conflict. These points will be discussed in detail in the discussion section.

2. The Contested Meaning of Open Peer Review

The diverse definitions of open peer review become apparent when examining just two examples. The first example is, to our knowledge, the earliest recorded use of the phrase “open peer review”:

“[A]n open reviewing system would be preferable. It would be more equitable and more efficient. Knowing that they would have to defend their views before their peers should provide referees with the motivation to do a good job. Also, as a side benefit, referees would be recognized for the work they had done (at least for those papers that were published). Open peer review would also improve communication. Referees and authors could discuss difficult issues to find ways to improve a paper, rather than dismissing it. Frequently, the review itself provides useful information. Should not these contributions be shared? Interested readers should have access to the reviews of the published papers.” (Armstrong, 1982)

“[O]pen review makes submissions OA [open access], before or after some prepublication review, and invites community comments. Some open-review journals will use those comments to decide whether to accept the article for formal publication, and others will already have accepted the article and use the community comments to complement or carry forward the quality evaluation started by the journal. ” (Suber, 2012)

These two examples alone reveal a multitude of factors at play, including: removal of anonymity, publication of review reports, interaction among participants, crowdsourcing of reviews, and public availability of manuscripts pre-review, among others. Each of these factors represents a distinct strategy for openness and targets different problems within traditional peer review. For instance, disclosing identities primarily aims to enhance accountability and reduce bias, as Armstrong suggests: “referees should be more highly motivated to do a competent and fair review if they may have to defend their views to the authors and if they will be identified with the published papers” (Armstrong, 1982). Publication of reports, on the other hand, addresses issues of reviewer incentive (providing credit for their work) and resource waste (making reports accessible to readers). Importantly, these factors are not necessarily interdependent; they can be implemented separately. For example, identities can be disclosed without publishing reports, and reports can be published while keeping reviewer names confidential.

This diversity has led many authors to acknowledge the inherent ambiguity of the term “open peer review” (Hames, 2014; Sandewall, 2012; Ware, 2011). The most significant attempt to bring order to this landscape of overlapping and competing definitions is Emily Ford’s paper, “Defining and Characterizing Open Peer Review: A Review of the Literature” (Ford, 2013). Ford examined thirty-five articles to develop a schema of eight “common characteristics” of OPR: signed review, disclosed review, editor-mediated review, transparent review, crowdsourced review, prepublication review, synchronous review, and post-publication review. However, despite identifying these eight characteristics, Ford’s paper ultimately falls short of providing a definitive definition of OPR. She attempts to reduce OPR to a single element: open identities. Ford states: “Despite the differing definitions and implementations of open peer review discussed in the literature, its general treatment suggests that the process incorporates disclosure of authors’ and reviewers’ identities at some point during an article’s review and publication” (p. 314). Elsewhere, she summarizes her argument as: “my previous definition … broadly understands OPR as any scholarly review mechanism providing disclosure of author and referee identities to one another” (Ford, 2015). However, the other elements in her schema cannot be reduced to this single factor. Many definitions of OPR do not include open identities at all. Therefore, while Ford claims to have identified several features of OPR, she effectively asserts that only one factor (open identity) is defining, leaving us in a similar position of definitional ambiguity. Furthermore, Ford’s schema presents other issues. It lists “editor-mediated review” and “pre-publication review” as distinguishing characteristics, even though these are common features of traditional peer review. It includes questionable elements like “synchronous review,” which is purely theoretical. And some characteristics, such as “transparent review,” appear to be complexes of other traits, incorporating open identities (which Ford terms “signed review”) and open reports (“disclosed review”).

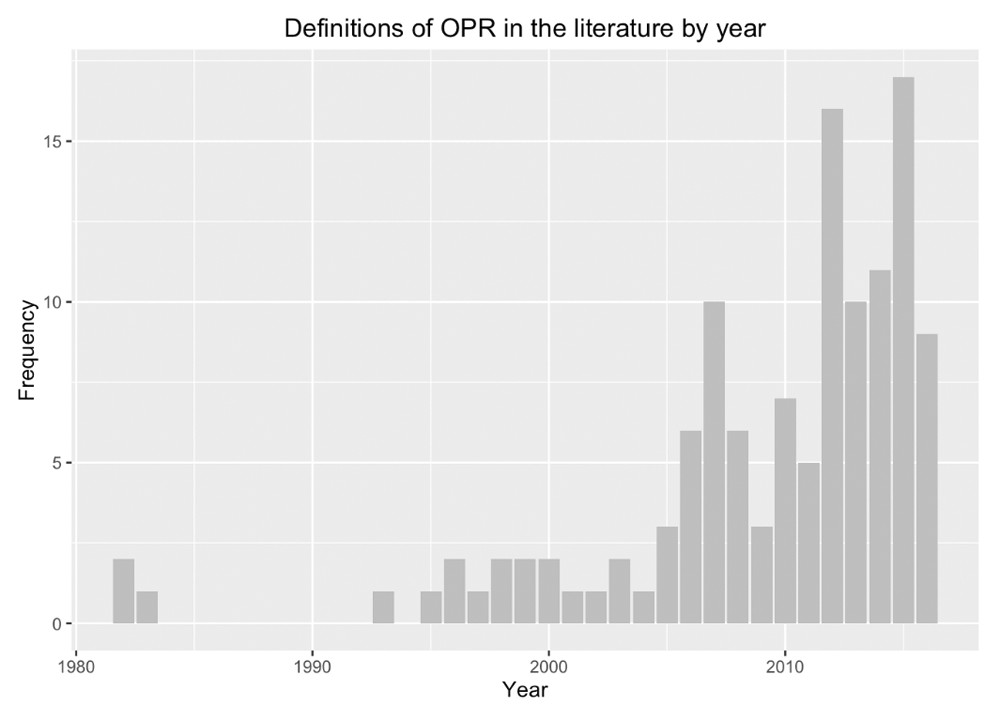

Figure 1. Trend of Open Peer Review Definitions in Literature Over Years

Alt Text: Line graph illustrating the increasing number of open peer review definitions found in academic literature per year, showing growth especially from the early 2000s.

Method: A Systematic Review of Previous Definitions

To resolve the ambiguity surrounding the definition of open peer review, a comprehensive literature review was conducted to identify and analyze existing definitions. A systematic search was performed in Web of Science (WoS) using the query “TOPIC: (“open review” OR “open peer review”)” without date limitations. This initial search yielded 137 results (search date: July 12, 2016). Each record was individually assessed for relevance, and 57 were excluded based on predefined criteria. Specifically, 21 BioMed Central publications were excluded as they mentioned an OPR process in the abstract but did not discuss the concept of OPR itself. Twelve results were excluded as they used “open review” to refer to literature reviews with flexible methodologies. Another 12 results were excluded as they reviewed objects “out of scope” (e.g., clinical guidelines, patent applications). Seven results were excluded due to being in languages other than English, and 5 were duplicates. This process resulted in a final set of 80 relevant articles that mentioned either “open peer review” or “open review.”

To broaden the search, the same search terms were applied to other academic databases, including Google Scholar, PubMed, ScienceDirect, JSTOR, and Project Muse. Additionally, the first 10 pages of search results from Google and Google Books (search date: July 18, 2016) were examined to identify references in “grey literature” (blogs, reports, white papers) and books, respectively. Finally, reference sections of identified publications, particularly bibliographies and literature reviews, were scrutinized for further references. Duplicate results were removed, and the exclusion criteria were applied to add an additional 42 definitions to the corpus. The complete dataset is publicly available online (Ross-Hellauer, 2017, http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.438024).

Each identified source was carefully examined for its definition of OPR. Where explicit definitions (e.g., “OPR is …”) were absent, implicit definitions were extracted from contextual statements. For example, the statement “reviewers can notify the editors if they want to opt-out of the open review system and stay anonymous” (Janowicz & Hitzler, 2012) was interpreted as implying a definition of OPR that incorporates open identities. In some cases, sources defined OPR in relation to specific publishers’ systems (e.g., F1000Research, BioMed Central, and Nature). These were taken to implicitly endorse those systems as representative of OPR.

By focusing solely on the terms “open review” and “open peer review,” this study intentionally limited itself to literature using these specific labels. It is important to acknowledge that other studies may have described or proposed innovations to peer review with aims similar to those identified in this review. However, if these studies did not explicitly use the terms “open review” or “open peer review” in conjunction with these systems, they were necessarily excluded from the scope. For instance, “post-publication peer review” (PPPR) is a closely related concept to OPR. However, unless sources explicitly equated the two, sources discussing PPPR were not included. This focus on the specific terminology of OPR, rather than on all sources addressing the underlying aims and ideas of such systems, defines the scope of this study.

Results

The number of OPR definitions identified over time demonstrates a clear increasing trend, with the highest number of definitions appearing in 2015. The distribution over the years indicates that, apart from a few early definitions in the 1980s, the term “open peer review” did not significantly enter academic discourse until the early 1990s. During that initial period, the term primarily seemed to refer to non-blinded review, emphasizing open identities. A substantial increase in definitions is observed from the early to mid-2000s onward. This surge likely correlates with the rise of the open agenda, particularly open access, but also open data and open science more broadly (Figure 1). The majority of definitions, 77.9% (n=95), originated from peer-reviewed journal articles. Books and blog posts represented the next largest sources. Other sources included letters to journals, news items, community reports, and glossaries (Figure 2). As depicted in Figure 3, most definitions (51.6%) were primarily concerned with peer review in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Medicine (STEM) fields, while 10.7% focused on Social Sciences and Humanities (SSH) material. The remaining 37.7% were interdisciplinary. Regarding the target of OPR mentioned in these articles (Figure 4), the majority referred to peer review of journal articles (80.7%), with 16% not specifying a target and a small number of articles also mentioning review of data, conference papers, and grant proposals.

Figure 2. Sources of Open Peer Review Definitions

Alt Text: Pie chart showing the breakdown of open peer review definitions by source type, with peer-reviewed journal articles as the largest segment.

Figure 3. Disciplinary Scope of Open Peer Review Definitions

Alt Text: Pie chart illustrating the disciplinary focus of open peer review definitions, highlighting STEM subjects as the majority, followed by interdisciplinary and SSH.

Figure 4. Material Types Under Review in Open Peer Review Definitions

Alt Text: Pie chart showing the types of materials undergoing open peer review in the definitions, with journal articles being the most frequently mentioned.

Among the 122 identified definitions, 68% (n=83) were explicitly stated, 37.7% (n=46) were implicitly stated, and 5.7% (n=7) contained both explicit and implicit information.

The extracted definitions were analyzed and categorized using an iteratively developed taxonomy of OPR traits. Following Nickerson et al. (2013), the taxonomy development began by identifying the primary meta-characteristic: distinct individual innovations to the traditional peer review system. An iterative process was then employed, applying dimensions from the literature to the corpus of definitions and identifying gaps and overlaps in the emerging OPR taxonomy. Based on this analysis, new traits or distinctions were introduced, resulting in a final schema of seven OPR traits:

- Open identities: Authors and reviewers are aware of each other’s identity.

- Open reports: Review reports are published alongside the relevant article.

- Open participation: The wider community is able to contribute to the review process.

- Open interaction: Direct reciprocal discussion between author(s) and reviewers, and/or between reviewers, is allowed and encouraged.

- Open pre-review manuscripts: Manuscripts are made immediately available (e.g., via pre-print servers like arXiv) in advance of any formal peer review procedures.

- Open final-version commenting: Review or commenting on final “version of record” publications.

- Open platforms (“decoupled review”): Review is facilitated by a different organizational entity than the venue of publication.

The core traits are readily apparent, with just three encompassing over 99% of all definitions. Open identities combined with open reports cover 116 (95.1%) of all records. Including open participation expands the coverage to 121 (99.2%) records overall. As shown in Figure 5, open identities is the most prevalent trait, present in 90.1% (n=110) of definitions. Open reports are also present in the majority of definitions (59.0%, n=72), while open participation is included in approximately one-third. Open pre-review manuscripts (23.8%, n=29) and open interaction (20.5%, n=25) are also fairly common components of definitions. The less frequent traits are open final version commenting (4.9%) and open platforms (1.6%).

Figure 5. Prevalence of Open Peer Review Traits in Definitions

Alt Text: Bar chart showing the distribution of open peer review traits across all definitions, highlighting open identities and open reports as the most frequent.

Analyzing these traits by the disciplinary focus of the definition source reveals interesting differences between STEM and SSH-focused sources (Figure 6). Definitions primarily concerned with peer review of SSH subjects show less emphasis on open identities (84.6% of SSH-focused definitions vs. 93.7% of STEM-focused definitions) and open reports (38.5% SSH vs. 61.9% STEM) compared to STEM. However, three traits were more frequently included in SSH definitions of OPR: open participation (53.85% SSH vs. 25.4% STEM), open interaction (30.8% SSH vs. 20.6% STEM), and open final-version commenting (15.4% SSH vs. 3.2% STEM). The other traits, open pre-review manuscripts and open platforms, showed similar prevalence across both groups. While these differences suggest a slightly divergent understanding of OPR between disciplines, caution is needed in drawing strong generalizations due to the risk of oversimplifying disciplinary specificities and the relatively small number of SSH-specific sources (n=13).

Figure 6. Trait Prevalence by Disciplinary Focus

Alt Text: Bar chart comparing the prevalence of each open peer review trait between definitions focused on STEM and SSH disciplines, showing variations in emphasis.

The various configurations of these traits within definitions are illustrated in Figure 7. Quantifying definitions in this manner accurately depicts the ambiguity in the usage of “open peer review” to date. The literature presents a total of 22 distinct configurations of the seven traits, effectively representing 22 different definitions of OPR within the examined literature.

Figure 7. Configurations of Open Peer Review Traits

Alt Text: Bar chart showing the unique combinations of open peer review traits found in the definitions, revealing the diversity of OPR conceptualizations.

The trait distribution reveals two highly popular configurations and a range of less common ones. The most popular configuration, open identities alone, accounts for one-third (33.6%, n=41) of definitions. The second most popular configuration, combining open identities and open reports, represents almost a quarter (23.8%, n=29) of all definitions. Following these, a “long-tail” of less frequently encountered configurations emerges, with over half of all configurations appearing only in a single definition.

Discussion: The Traits of Open Peer Review

This section provides a detailed analysis of each identified trait, exploring the problems they aim to address and the evidence supporting their effectiveness.

Open Identities

Open identity peer review, also referred to as signed peer review (Ford, 2013; Nobarany & Booth, 2015) or “unblinded review” (Monsen & Van Horn, 2007), is characterized by authors and reviewers being aware of each other’s identities. Traditional peer review typically operates as “single-blind,” where authors are unaware of reviewer identities, or “double-blind,” where both authors and reviewers remain anonymous. Double-blind reviewing is more prevalent in the Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences compared to STEM fields. However, single-blind review is the most common model across all disciplines (Walker & Rocha da Silva, 2015). A primary rationale for maintaining author anonymity is to mitigate potential publication biases against authors with traditionally feminine names, those from less prestigious institutions, or non-English speaking regions (Budden et al., 2008; Ross et al., 2006). Reviewer anonymity is intended to protect reviewers from undue influence, enabling them to provide candid feedback without fear of reprisal from authors. However, various studies have failed to demonstrate that these measures consistently improve review quality (Fisher et al., 1994; Godlee et al., 1998; Justice et al., 1998; McNutt et al., 1990; van Rooyen et al., 1999). As Godlee and colleagues concluded, “Neither blinding reviewers to the authors and origin of the paper nor requiring them to sign their reports had any effect on rate of detection of errors. Such measures are unlikely to improve the quality of peer review reports” (Godlee et al., 1998). Furthermore, factors like close disciplinary communities and internet search capabilities limit the effectiveness of author anonymity. Studies show reviewers can identify authors in 26% to 46% of cases (Fisher et al., 1994; Godlee et al., 1998).

Proponents of open identity peer review argue that it enhances accountability, facilitates credit for peer reviewers, and promotes fairness: “most importantly, it seems unjust that authors should be “judged” by reviewers hiding behind anonymity” (van Rooyen et al., 1999). Open identity review is also believed to potentially improve review quality, as reviewers may be more motivated and diligent knowing their names are attached to their reviews. A reviewer for this article also suggests that “proponents of open identity review in medicine would also point out that it makes conflicts of interest much more apparent and subject to scrutiny” (Bloom, 2017). Opponents argue that signing reviews might lead to less critical assessments, as reviewers may soften their true opinions to avoid causing offense. To date, studies have shown no significant impact in either direction (McNutt et al., 1990; van Rooyen et al., 1999; van Rooyen et al., 2010). However, these studies are primarily from medicine, limiting their generalizability, and further research across disciplines is needed.

Open Reports

Open reports peer review involves publishing review reports (either full reports or summaries) alongside the corresponding article. Often, though not always (e.g., EMBO reports, http://embor.embopress.org), reviewer names are published with the reports. The primary benefits of this practice lie in making previously invisible but potentially valuable scholarly information accessible for reuse. It increases transparency and accountability by allowing examination of behind-the-scenes discussions and processes of improvement and assessment. It also offers potential to further incentivize peer reviewers by making their work more visible and creditable within scholarly activities.

Peer reviewing is a demanding task. The Research Information Network reported in 2008 that a single peer review takes an average of four hours, with an estimated total global annual cost of around £1.9 billion (Research Information Network, 2008). Once an article is published, these reviews typically serve no further purpose beyond archival storage. Yet, these reviews contain information that remains relevant and valuable. Often, articles are accepted despite reviewer reservations. Published reports allow readers to consider these criticisms and “have a chance to examine and appraise this process of “creative disagreement” and form their own opinions” (Peters & Ceci, 1982). Publicly available reviews add another layer of quality assurance, as they are open to scrutiny by the wider scientific community. It could also enhance review quality, as the prospect of public reports might motivate reviewers to be more thorough. Publishing reports also aims to increase recognition and reward for reviewers’ work. Adding review activities to professional records is becoming common, with author identification systems (e.g., ORCID) now incorporating mechanisms to host this information (Hanson et al., 2016). Finally, open reports provide valuable guidance for early-career researchers on review tone, length, and criticism formulation as they begin peer reviewing themselves.

However, the evidence base for evaluating these arguments is limited. Van Rooyen and colleagues found that open reports correlate with higher reviewer refusal rates and increased review time but no significant effect on review quality (van Rooyen et al., 2010). Nicholson and Alperin’s smaller survey indicated generally positive attitudes, with researchers believing “that open review would generally improve reviews, and that peer reviews should count for career advancement” (Nicholson & Alperin, 2016.

Open Participation

Open participation peer review, also known as “crowdsourced peer review” (Ford, 2013; Ford, 2015), “community/public review” (Walker & Rocha da Silva, 2015), or “public peer review” (Bornmann et al., 2012), broadens participation in the review process to the wider community. Unlike traditional peer review where editors select and invite specific reviewers, open participation invites interested members of the scholarly community to contribute, either through full, structured reviews or shorter comments. Fitzpatrick & Santo (2012) argue that opening the reviewer pool can counter self-replication within fields by incorporating input from related disciplines, interdisciplinary scholars, and even the broader public.

In practice, open participation can range from comments open to anyone (anonymous or registered) to systems requiring credentials (e.g., Science Open requires an ORCID profile with at least five publications). Open participation is often used alongside traditional, editor-solicited peer review. It aims to address potential biases and limitations in editorial reviewer selection, including closed networks and elitism, and potentially enhance review reliability by increasing the number of reviewers (Bornmann et al., 2012). Reviewers can come from the wider research community and traditionally underrepresented groups in scientific assessment, including industry representatives or special interest groups, such as patients for medical journals (Ware, 2011). This approach expands the reviewer pool beyond editorially identified individuals to include all potentially interested reviewers, potentially increasing the number of reviews per publication, though this is not always realized. Evidence suggests open participation might improve peer review accuracy. For example, Herron (2012) developed a mathematical model showing that “the accuracy of public reader-reviewers can surpass that of a small group of expert reviewers if the group of public reviewers is of sufficient size,” specifically exceeding 50 reader-reviewers.

Criticisms of open participation often center on reviewer qualifications and incentives. Given increasing disciplinary specialization, especially in the sciences (Casadevall & Fang, 2014), concerns arise that individuals lacking specialized knowledge may not be qualified to evaluate findings accurately. Stevan Harnad questioned: “it is not clear whether the self-appointed commentators will be qualified specialists (or how that is to be ascertained). The expert population in any given speciality is a scarce resource, already overharvested by classical peer review, so one wonders who would have the time or inclination to add journeyman commentary services to this load on their own initiative” (Harnad, 2000). This may explain why open participation is more central to OPR conceptions in SSH than STEM. As noted earlier, open participation is the second most popular trait in SSH-focused definitions, appearing in over half, compared to just a quarter of STEM-focused definitions. Fitzpatrick and Santo argue that in the humanities, peer review often emphasizes “originality, creativity, depth and cogency of argument, and the ability to develop and communicate new connections across and additions to existing texts and ideas,” contrasting with the sciences’ focus on “verification of results or validation of methodologies” (Fitzpatrick & Santo, 2012). Assessing narrative cogency and interdisciplinary connections is more broadly applicable than discipline-specific methods. While both are important in all scholarship, the former’s greater role in SSH may drive interest in open participation in those fields.

Another challenge for open participation is motivating self-selected commentators to participate and provide valuable critique. Nature‘s experiment (June-December 2006) using open participation alongside traditional review was deemed unsuccessful due to low author participation (5%), few comments overall (almost half of articles received none), and the insubstantial nature of most comments (Fitzpatrick, 2011). At Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics (ACP), which publishes pre-review discussion papers for community comments, only about one in five papers receives comments (Pöschl, 2012). Bornmann et al. (2012) compared ACP’s community comments to formal referee reviews and concluded that referee reviews, focusing more on formal qualities, conclusions, and impact, better supported manuscript selection and improvement. This suggests open participation, while a potentially valuable supplement, is unlikely to fully replace traditional invited peer review.

Open Interaction

Open interaction peer review fosters direct, reciprocal discussion among reviewers and/or between authors and reviewers. In traditional peer review, communication is primarily between reviewers and editors, and authors typically lack direct interaction with reviewers. Open interaction aims to “open up” the review process, enabling editors and reviewers to collaborate with authors to improve manuscripts. Armstrong (1982) advocated for this to “improve communication. Referees and authors could discuss difficult issues to find ways to improve a paper, rather than dismissing it” (Armstrong, 1982). Kathleen Fitzpatrick (2012) suggests such interaction can foster “a conversational, collaborative discourse that not only harkens back to the humanities’ long investment in critical dialogue as essential to intellectual labor, but also models a forward-looking approach to scholarly production in a networked era.”

Some journals, like EMBO Journal, routinely facilitate pre-publication interaction among reviewers, enabling “cross-peer review” where referees comment on each other’s reports for a balanced process (EMBO Journal, 2016). eLife employs “online consultation sessions” where reviewers and editors collaboratively reach a mutual decision before the editor compiles a single, non-contradictory revision roadmap for authors (Schekman et al., 2013). Frontiers takes this further with an interactive collaboration stage uniting authors, reviewers, and editors in direct online dialogue for rapid iterations and consensus-building (Frontiers, 2016).

Evidence evaluating interactive review effectiveness is even scarcer than for other OPR traits. Anecdotal reports suggest generally, but not universally, positive feedback from participants (Walker & Rocha da Silva, 2015). To the author’s knowledge, the only experimental study on reviewer/author interaction is by Leek and colleagues, who used an online game to simulate open and closed peer review. They found “improved cooperation does in fact lead to improved reviewing accuracy. These results suggest that in this era of increasing competition for publication and grants, cooperation is vital for accurate evaluation of scientific research” (Leek et al., 2011). While these results are encouraging, they are far from conclusive, highlighting the need for further research on the impact of cooperation on review process efficacy and cost.

Open Pre-review Manuscripts

Open pre-review manuscripts are made openly accessible online (via the internet) before or concurrent with formal peer review. Subject-specific preprint servers like arXiv.org and bioRxiv.org, institutional and general repositories (Zenodo, Figshare), and publisher-hosted repositories (PeerJ Preprints) allow authors to bypass traditional publication delays and immediately disseminate their manuscripts. This can complement traditional publication, inviting comments on preprints to inform revisions during journal peer review. Alternatively, services overlaying peer review onto repositories can create cost-effective publication platforms (Boldt, 2011; Perakakis et al., 2010. The mathematics journal Discrete Analysis, for example, is an overlay journal hosted on arXiv (Day, 2015). Open Scholar’s Open Peer Review Module for repositories, developed with OpenAIRE, is open-source software adding overlay peer review to DSpace repositories (OpenAIRE, 2016). ScienceOpen is another model, ingesting preprint metadata, contextualizing it with altmetrics, and offering author-initiated peer review.

In other cases, manuscripts submitted to publishers are made immediately available online (after a preliminary check) before peer review begins. Electronic Transactions in Artificial Intelligence (ETAI) pioneered this in 1997 with a two-stage process: online community discussion followed by standard anonymous peer review. ETAI ceased publication in 2002 (Sandewall, 2012). Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics uses a similar multi-stage system with “discussion papers” for community comments and peer review (Pöschl, 2012). F1000Research and the Semantic Web Journal are other prominent examples.

Open pre-review manuscripts offer benefits such as allowing researchers to establish priority in reporting findings without publication delays and fear of being “scooped.” Earlier research dissemination increases visibility, enables open participation in review, and may even improve initial manuscript quality (Pöschl, 2012). Making manuscripts openly available pre-review allows real-time tracking of the peer review process and comments from both invited reviewers and the wider community.

Open Final-Version Commenting

Open final-version commenting refers to review or commentary on final “version of record” publications. While peer review traditionally aims to improve and select manuscripts before publication, the internet has expanded opportunities for post-publication feedback. Even the final version of record is subject to ongoing evaluation and potential improvement.

The internet has vastly broadened channels for readers to offer feedback on scholarly works. Previously limited to formal letters to the editor or commentary articles, numerous online channels now exist. Journals increasingly offer comment sections, though utilization is often low. Walker & Rocha da Silva (2015) found 24 of 53 surveyed publishing venues offered user commenting, but usage was typically limited. A 2009 survey found almost half of respondents considered post-publication commentary beneficial (Mulligan et al., 2013). However, researchers can “publish” their thoughts anywhere online – via academic social networks (Mendeley, ResearchGate, Academia.edu), Twitter, or blogs. Peer review can thus be decoupled not only from journals but also from specific platforms. A work’s reputation continuously evolves through ongoing discussion. Considering final-version commenting as part of a perpetual peer review process encourages a shift from viewing peer review as a discrete pre-publication process towards an ongoing dialogue. “Living” publications like Living Reviews journals exemplify this, allowing authors to regularly update articles. Even finalized versions remain subject to retraction or correction, often driven by social media, as seen in the #arseniclife case where social media critique led to retractions in Science. Retraction Watch blog publicizes such cases.

PubPeer is a key platform for “post-publication peer review.” Its users’ critique of a Nature paper on STAP cells led PubPeer to argue that “post-publication peer review easily outperformed even the most careful reviewing in the best journal. The papers’ comment threads on PubPeer have attracted some 40000 viewers. It’s hardly surprising they caught issues that three overworked referees and a couple of editors did not. Science is now able to self-correct instantly. Post-publication peer review is here to stay” (PubPeer, 2014).

Open Platforms (“Decoupled Review”)

Open platforms peer review involves review facilitated by an organization separate from the publication venue. Dedicated platforms have emerged to decouple review from journals. Services like RUBRIQ and Peerage of Science offer “portable” or “independent” peer review. Axios Review (2013-2017) offered a similar service. These platforms invite manuscript submissions, organize reviews within their reviewer communities, and provide review reports. RUBRIQ and Peerage of Science allow participating journals to access these scores and manuscripts, enabling them to offer publication or suggest submission. Axios forwarded manuscripts, reviews, and reviewer identities to authors’ preferred journals. Models vary (RUBRIQ pays reviewers; Axios used a community model with review discounts), but all aim to reduce publication inefficiencies, especially duplicated review efforts. Traditional peer review can involve multiple review cycles across journals. Decoupled review services aim for a single review set applicable across journals until publication (“portable” review).

Other decoupled platforms address different issues. Publons addresses reviewer incentive by making peer review measurable. Publons collects review information from reviewers and publishers to create reviewer profiles detailing verified contributions for CVs. Overlay journals like Discrete Mathematics are another example. Peter Suber defines overlay journals as “An open-access journal that takes submissions from the preprints deposited at an archive (perhaps at the author’s initiative), and subjects them to peer review…. Because an overlay journal doesn’t have its own apparatus for disseminating accepted papers, but uses the pre-existing system of interoperable archives, it is a minimalist journal that only performs peer review” (quoted in Cassella & Calvi, 2010). Finally, platforms for commenting on published works, like blogs, social networks, and PubPeer (discussed under “open final-version commenting”), also represent decoupled review venues.

Which problems with traditional peer do the various OPR traits address?

We began by outlining problems with traditional peer review and noted OPR’s various forms as potential solutions. However, no single trait addresses all problems, and aims may conflict. Which traits address which problems? Which might worsen them? Based on the preceding analysis, here’s a summary:

- Unreliability and inconsistency: Open identities and open reports are intended to improve review quality through increased reviewer accountability and diligence. However, evidence is limited. Open participation and open final-version commenting may improve reliability by increasing reviewer numbers and diversity, though open participation struggles to attract reviewers and editorial mediation remains necessary. Open interaction may enhance accuracy through cooperation.

- Delay and expense: Open pre-review manuscripts accelerate research dissemination and may improve initial submissions. Open platforms address the “waterfall” problem of serial journal submissions and rejections. Open participation could theoretically reduce editorial reviewer sourcing, but cost reduction is questionable due to low participation and continued editorial needs. Open identities and open reports might increase delay and expense due to reviewer reluctance. Open interaction could lengthen review times through increased back-and-forth and editorial mediation.

- Lack of accountability and risks of subversion: Open identities and reports increase accountability and transparency, highlighting conflicts of interest. Open participation could address biased editorial reviewer selection but might increase engagement by those with conflicts of interest, especially with anonymity. Open identities might discourage critical reviews due to reviewer visibility, potentially subverting the process.

- Social and publication biases: Open reports enhance quality assurance by allowing scrutiny of decision-making. However, open identities removes anonymity intended to counter social biases, although anonymity’s effectiveness is debated.

- Lack of incentives: Open reports linked to open identities increase peer review visibility, enabling citation and recognition for career advancement. Open participation could incentivize reviewers by allowing self-selection of review topics, but current experience suggests lower reviewer participation under this model.

- Wastefulness: Open reports make valuable scholarly information reusable and provide guidance for novice reviewers.

This synthesis leads to several conclusions: (1) OPR traits can address many traditional peer review problems, but (2) different traits target different problems in different ways, (3) no trait solves all problems, and (4) traits may exacerbate some issues. (5) Limited evidence often complicates assessment. More research is crucial to empirically evaluate trait efficacy in resolving these issues.

Open Science as the unifying theme for the traits of OPR

The identified OPR traits are diverse in aims and implementation. Is there a unifying thread? We argue they aim to align peer review with the broader Open Science agenda. Open Science seeks to reshape scholarly communication, encompassing open access, open data, open source software, open workflows, citizen science, open educational resources, and open peer review (Pontika et al., 2015). Fecher & Friesike (2013) analyzed the motivations behind Open Science, identifying five “schools of thought” (Figure 8):

Figure 8. Five Schools of Thought in Open Science

Alt Text: Diagram outlining the five schools of thought within Open Science: Democratic, Pragmatic, Infrastructure, Public, and Measurement, and their respective focuses.

- Democratic school: Aims for equitable access to knowledge, making scholarly outputs freely available.

- Pragmatic school: Seeks to enhance knowledge creation efficiency and critique through collaboration and transparency.

- Infrastructure school: Focuses on readily available platforms and tools for dissemination and collaboration.

- Public school: Aims for societal engagement in research and accessible communication of scientific results.

- Measurement school: Promotes alternative metrics to track scholarly impact beyond traditional publication-focused metrics.

OPR traits, in overlapping ways, promote transparency, accountability, inclusivity, and efficiency in peer review, aligning with Open Science principles. OPR traits fit within Fecher & Friesike’s Open Science schema as follows:

- Democratic school: Open reports increase scholarly product accessibility.

- Pragmatic school: Open identities enhance accountability; open reports increase transparency; open interaction fosters collaboration; open pre-review manuscripts enable earlier dissemination.

- Infrastructure school: Open platforms enhance peer review efficiency.

- Public school: Open participation and final-version commenting increase inclusivity by broadening reviewer pools.

- Measurement school: Open identities, open reports, and open platforms facilitate monitoring and recognition of peer review contributions.

Conclusion

The definition of “open peer review” remains contested. This article aimed to clarify the meaning of this increasingly important term. Analyzing 122 definitions, we identified seven OPR traits addressing various problems with traditional peer review. The corpus revealed 22 unique trait configurations, representing 22 distinct OPR definitions in the literature. Core elements across definitions are open identities and open reports, present in over 95%. Open participation is also a significant element, particularly in SSH. Secondary elements include open interaction and pre-review manuscripts. Fringe elements are open final version commenting and open platforms.

Given OPR’s contested nature, acknowledging its ambiguity as an umbrella term for diverse peer review innovations is crucial. Quantifying this ambiguity and mapping traits provides a foundation for future discussions, acknowledging diverse interpretations and clarifying specific traits under discussion.

Treating OPR’s ambiguity as a feature, not a bug, is key. The array of configurations offers a toolkit for communities to design OPR systems tailored to their needs and goals. Disciplinary differences in OPR interpretations, particularly the greater emphasis on open participation in SSH, reinforce this view. Disambiguating traits will enable more focused analysis of their effectiveness in addressing claimed problems, which is urgent given the limited evidence supporting many claims.

Based on this analysis, we propose the following definition:

OPR definition: Open peer review is an umbrella term for a number of overlapping ways that peer review models can be adapted in line with the aims of Open Science, including making reviewer and author identities open, publishing review reports and enabling greater participation in the peer review process. The full list of traits is:

- Open identities: Authors and reviewers are aware of each other’s identity

- Open reports: Review reports are published alongside the relevant article.

- Open participation: The wider community to able to contribute to the review process.

- Open interaction: Direct reciprocal discussion between author(s) and reviewers, and/or between reviewers, is allowed and encouraged.

- Open pre-review manuscripts: Manuscripts are made immediately available (e.g., via pre-print servers like arXiv) in advance of any formal peer review procedures.

- Open final-version commenting: Review or commenting on final “version of record” publications.

- Open platforms (“decoupled review”): Review is facilitated by a different organizational entity than the venue of publication.

Data availability

Dataset including full data files used for analysis in this review: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.438024 (Ross-Hellauer, 2017).

Notes

1This quote was found on the P2P Foundation Wiki (http://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Open_Peer_Review, accessed 18th July 2016). Its provenance is uncertain, even to Suber himself, who recently advised in personal correspondence (19th August 2016): “I might have said it in an email (as noted). But I can’t confirm that, since all my emails from before 2009 are on an old computer in a different city. It sounds like something I could have said in 2007. If you want to use it and attribute it to me, please feel free to note my own uncertainty!”

Competing interests

This work was conducted as part of the OpenAIRE2020 project, an EC-funded initiative to implement and monitor Open Access and Open Science policies in Europe and beyond.

Grant information

This work is funded by the European Commission H2020 project OpenAIRE2020 (Grant agreement: 643410, Call: H2020-EINFRA-2014-1).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Birgit Schmidt (University of Goettingen), Arvid Deppe (University of Kassel), Jon Tennant (Imperial College London, ScienceOpen), Edit Gorogh (University of Goettingen) and Alessia Bardi (Istituto di Scienza e Tecnologie dell’Informazione) for discussion and comments that led to the improvement of this text. Birgit Schmidt created Figure 1.

Supplementary material

Supplementary file 1: PRISMA checklist. The checklist was completed with the original copy of the manuscript.

Click here to access the data.

Supplementary file 2: PRISMA flowchart showing the number of records identified, included and excluded.

Click here to access the data.

Faculty Opinions recommended